THE VITAL WORK OF ANDRES DUANYA COMMENTARY

The work of CNU is typified, and perhaps primarily motivated by the pioneering work of Andres Duany, first with his town of Seaside, Florida (developer Robert Davis), then with Windsor, Florida, and with town plans and pattern books for a variety of towns and communities across the United States. Duany's work, by his own assessment, was largely inspired by the pattern language. We believe that wide discussion both of the positive aspects of what he has done, and of its shortcomings, is essential to the successful furtherance of our mutual aims

By Christopher Alexander

Introduction

The effort to make cities better, and to move away from the desert of urbanization familiar in mid 20th-century world, was inspired by various critical thinkers, architects and urbanists, who pointed out that traditional societies, traditional values, and classical traditional architecture all contained vital knowledge that was not ephemeral, but more or less permanent, and culture-independent: and therefore valid for our towns and buildings today, and in the future, just as much as it had been in earlier ages.

In the decade after the appearance of the pattern language, this was seen clearly, and independently, by a variety of architects in different countries, including Andres Duany, Leon Krier, Dan Solomon, various anthropologists, by planners such as Jane Jacobs, and then by many others, in the period from 1980 to the end of the century.

Section 1

Duany's most important accomplishment

The extraordinary contribution made by Duany was that he took the concept of patterns and pattern languages, and created a simple, and operationally feasible way of introducing this concept into effective town-planning procedure, consistent with United States conditions.

Don't just talk, do it. Talk, as we all know, comes cheap. Andres has gone to where the rubber hits the road, worked, confronted, composed with the forces in play. In twenty years with various associates he has designed over 80 new towns and revitalization projects for existing communities. Eighty real flesh and blood communities is a lot.

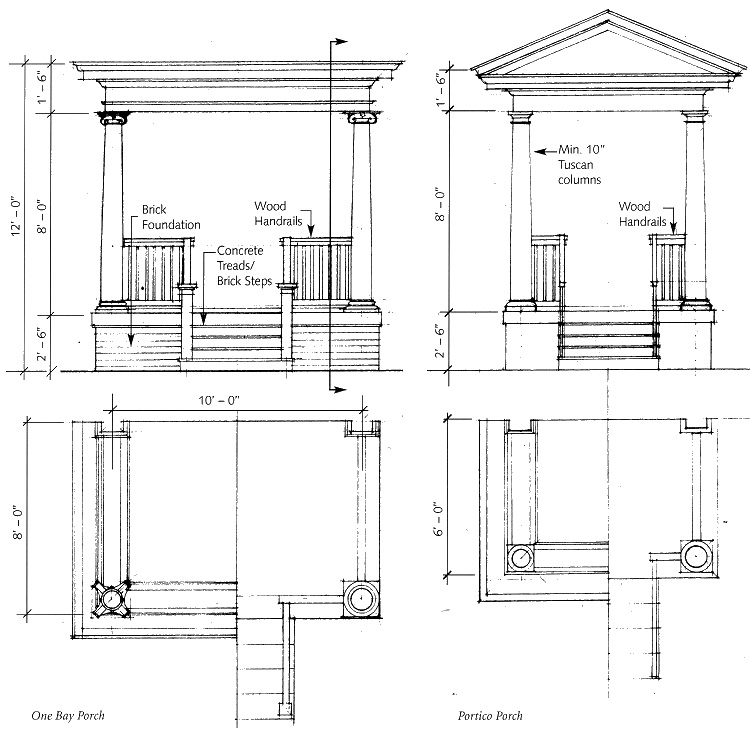

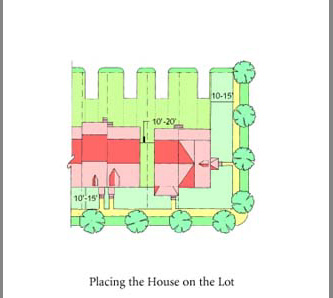

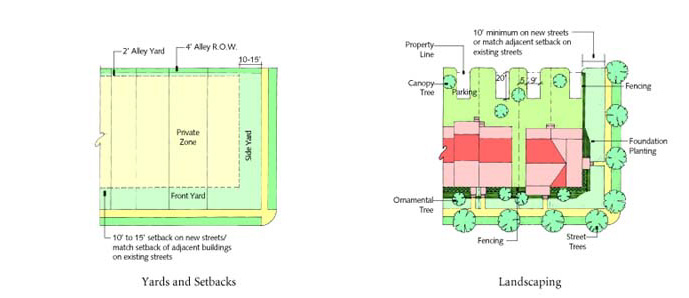

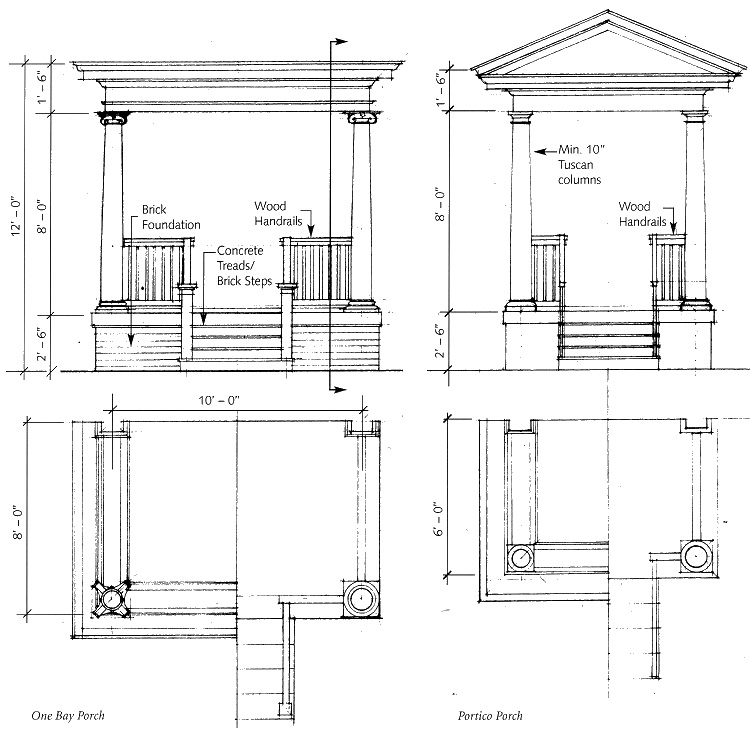

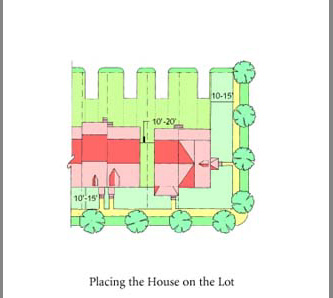

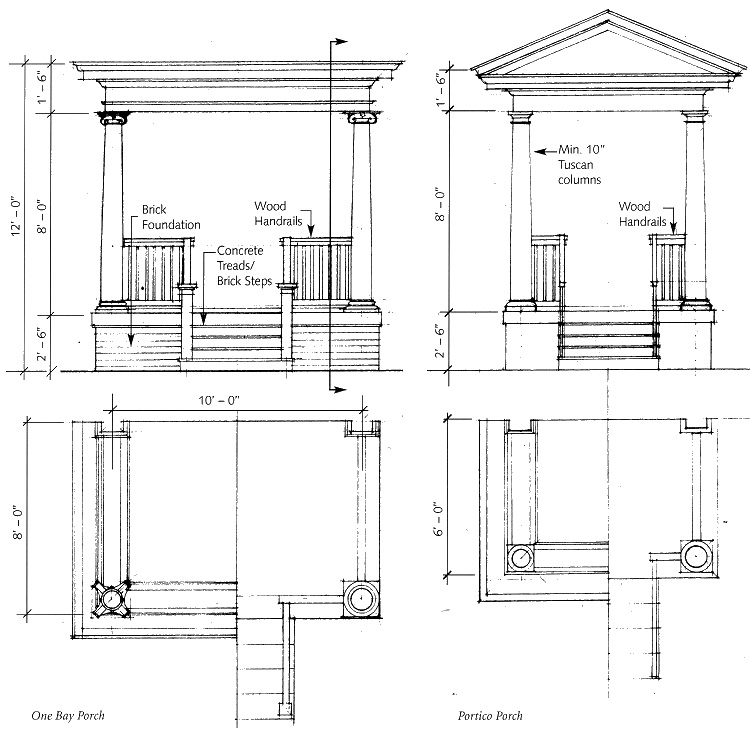

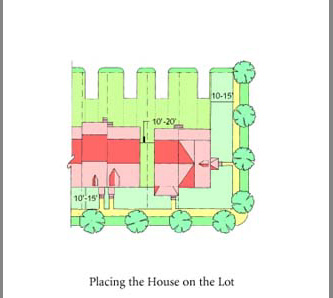

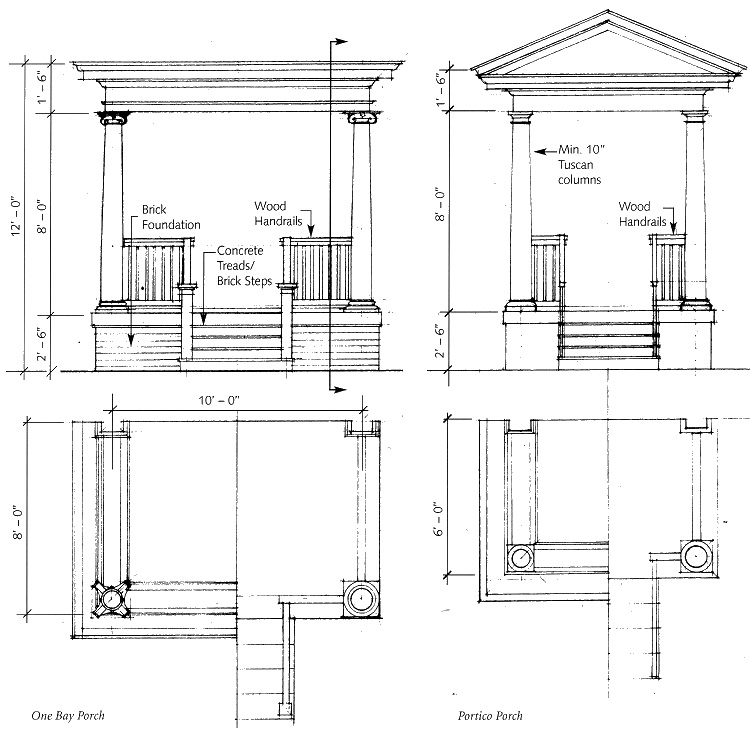

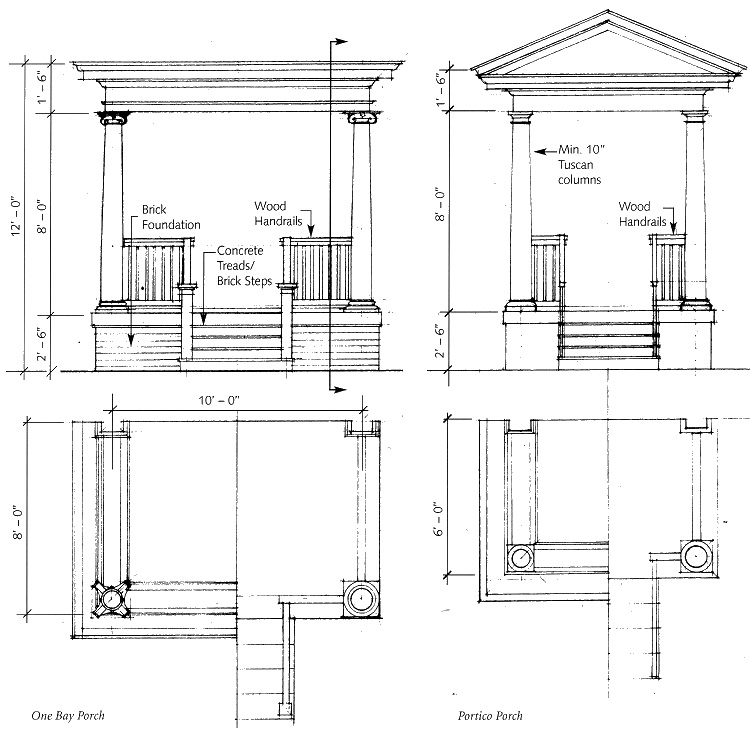

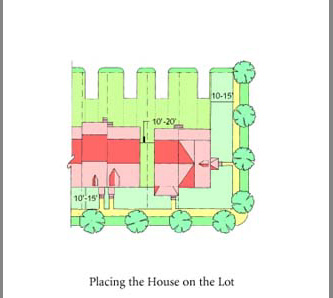

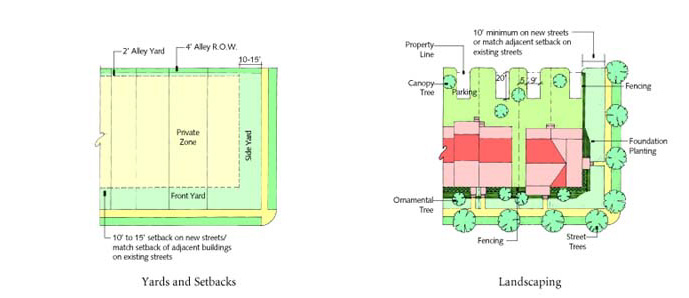

Visible in a number of pattern books composed specially for these different communities (see, for example, the Bedford pattern book for Bedford, in Pittsburgh ), the treatment of patterns in these plans is extraordinarily detailed, covering roads, lots, gardens, house volumes, style, massing, windows, architectural details.

......

......

Excerpts from the Bedford pattern book

It is fair to say that Duany's work, and the work of CNU that in large measure originates with his contribution, has altered, and will continue to alter, the American landscape. In spite of carping by others, one cannot get away from this fact.

That is a truly extraordinary accomplishment.

There is, also, considerable detail which came with this broad program, and which was, once again, made by Duany into something recognizable to the American public.

Our sacred cow: the car. Duany is clear that it is the public realm—the walkable public realm—that requires the most Tender Loving Care in community projects and that the power that has slid over to the traffic engineer must be rewon. One telling number from Duany's writings is that eliminating the need for one more car in a family (typically eating up around $5000 a year) will be the equivalent of that family's capacity of taking on a $50,000 mortgage. And we don't need new urbanists to tell us that our towns treat our cars better then they treat us.

A social and administrative process. To get real things done in the real world, different stakeholders must have their say. Duany's charrette process allows for client involvement, voicing of concerns, shared emergence of priorities, and "buy-in" for the plans and codes that will guide the design process. The "codes" that emerge from the charette and from study are project specific. They consider local architectural traditions and building techniques that will be work into exisiting zoning ordinances.

A sense of place. Duany struggles as all of us who are concerned with the built environment with a sense of place which comes from, among other factors, a balance of privacy and community. The Ahwahnee Principles (focusing on human scale, diversity, complexity, process of involvement) animate his work. His plans include neighborhoods that are easily walkable, finite with a definite character, mixed uses, complex and multipurpose grid streets networks, housing for different economic levels. He made incredible efforts to actually figure out the geometry. To have a sense of place is to have a sense of space. To give an example of one pattern in frequent use,

is that for every foot of vertical space there ought to be no more than 6 feet of horizontal space. In other words, the street width as measured from building front to building front should not exceed six times the height of the buildings.

Work with what you've got and push for bigger change. Duany is a realist. He works with what is there and pushes on the boundaries. While accepting the existing codes he lobbies for better ones. He advocates replacing codes based on functional separation with codes based on typological compatibility. He knows that specialized land use districts are almost always unnecessary. As long as the buildings along a stretch of street are compatible in shape and size,similar in site configuration, and follow the same disposition relative to the street, what functions go in them are of not great concern.

Duany's realistic problem solving is creative. The plan for the transfer of development rights for Hillsborough County, Florida is most impressive.

Altogether, the track record of study, action, and implementation is remarkable.

Section 2

Duany's most serious shortcoming

The greatest weakness, without a doubt, is the failure of Duany, and indeed of other CNU affiliates, to recognize the devastating effect of development, and of the developer, on the American landscape, and on the world landscape.

It is of course, a matter of practicality. If you want to affect things, go to the people who have the power and financial might, and try to persuade them. Andres Duany, Dan Solomon, Raymond Gindroz, Peter Calthorpe, have all tailored their activities to the existence of developers, without ever—apparently—grasping the extent to which this affiliation requires giving up on the fundamental processes which give life to the environment—the genuine fine grained participation of people themselves, and the creation of a world in which human intimacy is reflected in their production, in the absurd, charming, and often deeply adapted form of the buildings they create. The buildings made by a developer—even if acting within an imposed pattern book—cannot be well adapted, because the process stems from different motivations.

The greatest shortcoming of Duany (and CNU) is their failure to recognize that the form and complexity of the traditional town comes from (and can only come from) the process which generated it. Process and result can not be separated. Even with the charette approach to involve more stakeholders and the deliberate use of several architects to produce variation, the new urbanist developments are born from a process of a master scheme of blueprint, banking, permissions, construction. The expenditures of money and the decisions are not at the fine grained level of the spontaneous and free actual user. The process is guided by a monolithic need for control and restrictive covenants that protect the financial backers. It is inescapable that this process will lead to a different end result.

Section 3

Seaside, Florida

Duany's most well known project, at least until now, has been Seaside. Seaside is a town of some 4000 houses or households; many occupied at first as summer places, and then filled more as people chose to spend more of the year there.

Robert Davis, the developer of Seaside, has spent the better part of his life making this project, and trying, as best he can, to follow principles of community, discussion, town meetings, and to create a comfortable human atmosphere in which people can feel at home.

Davis among developers, is remarkable. He is marked by idealism, and moved by idealism. He has devoted his life to the creation of a modern American utopia, at least within the framework offered by contemporary American society and the current-day ideas of the flow of property and money.

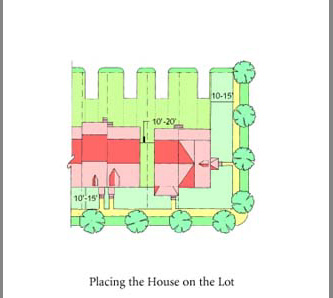

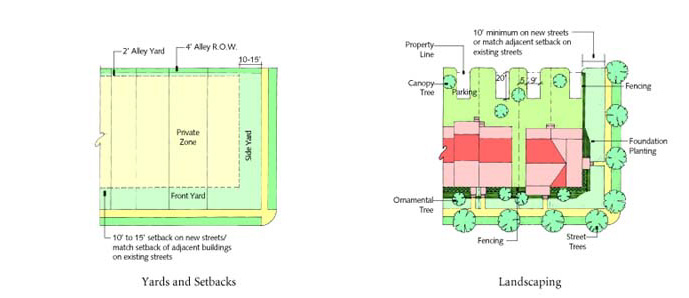

To provide the physical layout and backdrop for Seaside, Duany made the first of his pattern books: a system of codes prescribing in considerable detail, the placing of buildings, setbacks, lots lines, fences, road widths, style even, window design, and so forth.

As far as one might hope, this has been successsful.

......

......

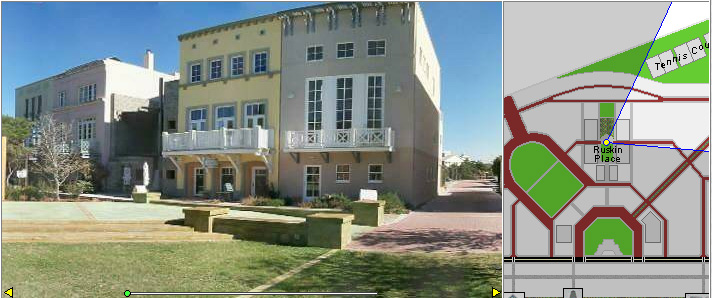

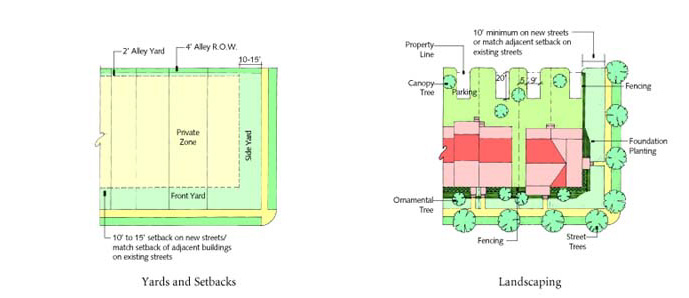

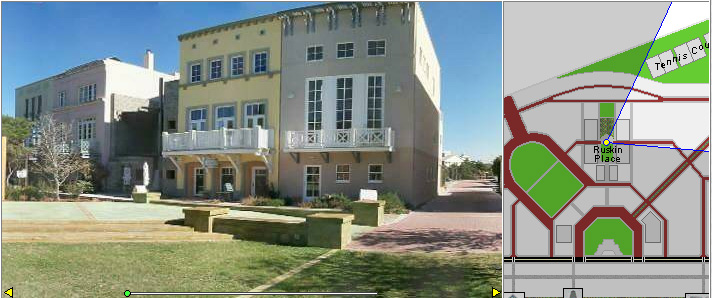

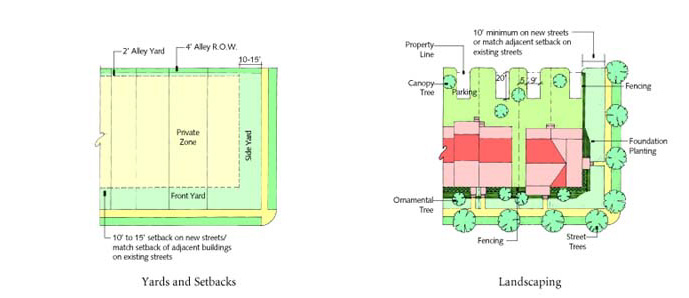

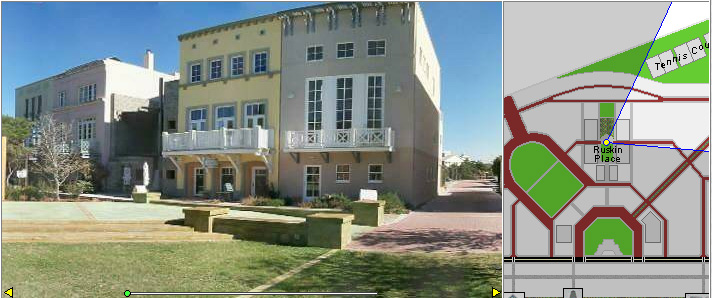

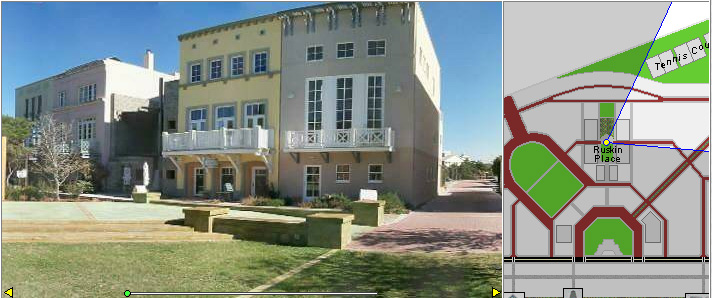

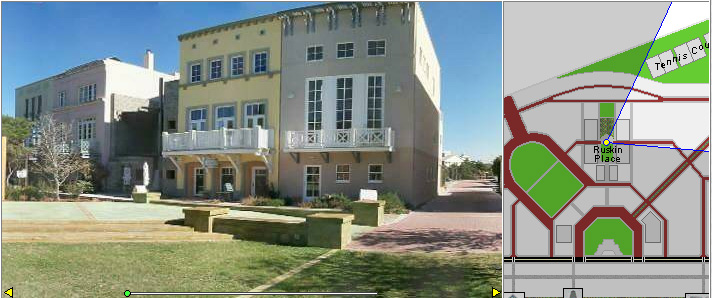

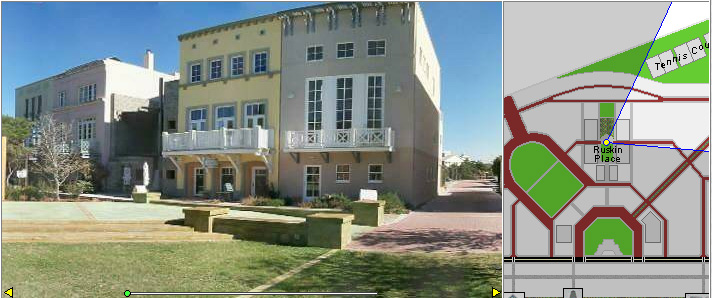

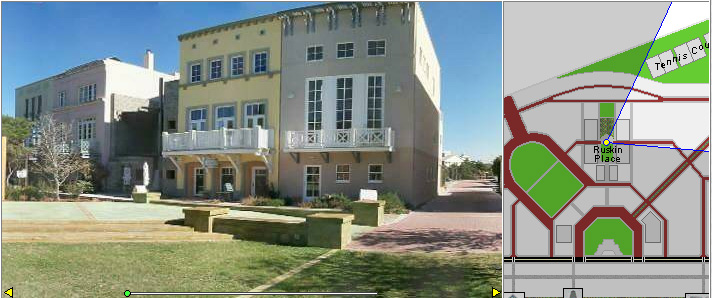

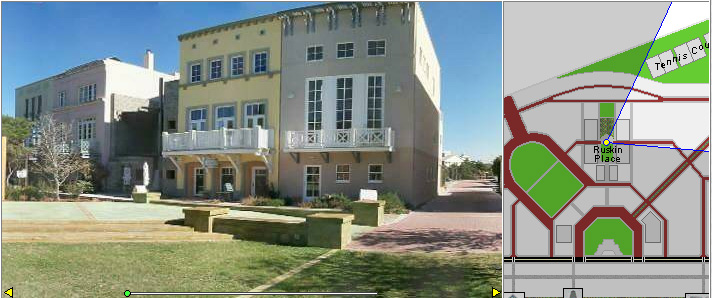

views of Seaside

Four views of Ruskin Place

Section 4

What does Seaside do and achieve?

First of, there is a humane environment, pleasant, avoiding many of the mishaps and ugliness of modern American development. It has charm. It has some atmosphere.

From a technical point of view, what is important, is simply the fact that the architect has achieved control over a very large area—some 600 acres: has created some degree of freedom and variation within that 600 acres; and has succeeded, in regulating, also, so that roads and streets are better scaled, there is some sense of pleasant architectural detail—white fences, good windows, and so on.

The scale is pleasant—and so this one architect (he would call himself a planner)—has asserted his design awareness over more than a thousand buildings, and has done so in a way that he can be proud of.To manage to have an effect on a very large number of buildings, without personally designing them, and yet to be concerned with the architecture—to achieve a certain coherence, scale, and pleasantness in them, together with sensible patterns carefully controlled—all that is an amazing achievement.

We take our hats off to Andres.

We all, members of the profession, need to exercise our action at this level. if each architect in the world were able to influence, in a positive fashion, such a relatively large area, the world would indeed be a better place, and the 500,000 to 1,000,000 architects in the world would then be able to have an effect on a major portion of the world's inhabited surface.

All that is immensely positive. It is an amazing achievement!

So where are the shortfalls?

Section 5

What does Seaside not achieve?

In order to achieve this very large, and humane effect, Andres has used what is a partly mechanical method. He has therefore been forced, in this first round of experiments (we take Seaside as an example only: the other projects work in roughly similar ways), to make a somewhat mechanical version of the ideal.

It is the nature of this "mechanical" aspect which has to be examined carefully.

In essence it consists of making a rigid framework, and allowing, then considerable individual variation within it. But the carcase, the street grid, is rigid: it does not arise from the give and take of real events. In this regard it is unlike an organic community. It is as if one were to have a rigid mechanical skeleton and hang variational flesh on it. That is not the same as making a coherent whole, in which the public space arises organically from detailed, and subtle adaptations to terrain, human idiosyncracy, individual trees, accidental paths, and so on.

And there follows from this a slightly more problematic quality. The actual public space is not always positive. It has not been lovingly crafted and shaped, because in the process followed, there was no opportunity to do such a thing.

The subtle mechanical character which underlies the production of the street grid, is visible, though, in a more disturbing quality. Occasionally one hears that there is something "unreal" about Seaside. Some of it is carping. Perhaps jealousy. But there is something about this comment that is real, and which goes to the very root of our current inability to make living space in towns.

Section 6

A view from the Press

Well-behaved dogs are allowed

This is the actual web caption placed with this picture, by the realtor who is renting the place!

DogGone Newsletter Vol.

8, No. 4, July/August 2000

A Seaside Utopia in Florida

In the movie, "The

Truman Show," Jim Carrey's character, Truman, lives in a utopian community,

unaware he was being filmed 24 hours a day. That visionary village really

exists. Seaside, Florida, where much of the movie was filmed, lies on  the Gulf of Mexico in Florida's panhandle,

tucked between Grayton Beach and Seagrove Beach. Pet owners can't rent

Truman's house (though you can photograph its exterior), but lucky dogs and

their owners can stay in a gorgeous waterfront $2-million plus vacation home.

It's virtually the only Seaside rental that will accept pets.

the Gulf of Mexico in Florida's panhandle,

tucked between Grayton Beach and Seagrove Beach. Pet owners can't rent

Truman's house (though you can photograph its exterior), but lucky dogs and

their owners can stay in a gorgeous waterfront $2-million plus vacation home.

It's virtually the only Seaside rental that will accept pets.

Idyll-By-The-Sea is a vacation rental cottage (it's really too

luxurious to be called a cottage) owned by Carol Irvine, Jerry Jongerius and

their German Shepherd Dog, Jackie. They are happy to rent their little

Shangri-La to owners of perfectly behaved pooches. The home's hardwood floors

tolerate sandy paws and dog sheets are provided to protect the furnishings.

And Idyll-By-The-Sea is well furnished, indeed. You can tell the owner's

business is antiques and interior design. The beach house is a comfortable mix

of new and old, with just the right touch of whimsy for a relaxed feel.

Thankfully, there's not a shred of Salvation Army style that pervades many

rental units I've leased over the years. Of course, the rental fee reflects

this. Idyll-By-The-Sea goes for $724-$874 per night.

Wendy Ballard

Reference to the film The Truman Show is not meant to be a facile criticism, but a genuine worry that all is not quite well.

The careful choice of Seaside as an ideal film set for the surreal film of alienation and falseness and image-production is not an accident. The choice of Jim Carrey as the hero is not an accident either. Curiously, to make our point, we turn to a passage about contemporary alienation hiding in a bland exterior, written by the art critic, John Berger in his essay on Francis Bacon. Consider what he says in the following quote:

Bacon's art is, in effect, conformist. It is not with Goya or the early Eisenstein that he should be compared, but with Walt Disney. Both men make propositions about the alienated behaviour of our societies; and both, in a different way, persuade the viewer to accept what is. Disney makes alienated behaviour look funny and sentimental and therefore, acceptable. Bacon interprets such behaviour in terms of the worst possible having already happened, and so proposes that both refusal and hope are pointless. The surprising formal similarities of their work—the way limbs are distorted, the overall shapes of bodies, the relation of figures to background and to one another, the use of neat tailor's clothes, the gesture of hands, the range of colours used—are the result of both men having complementary attitudes to the same crisis.

Disney's world is also charged with vain violence. The ultimate catastrophe is always in the offing. His creatures have both personality and nervous reactions: what they lack (almost) is mind. If, before a cartoon sequence by Disney, one read and believed the caption, "There is nothing else," the film would strike us as horrifically as a painting by Bacon.

Bacon's paintings do not comment, as is often said, on any actual experience of loneliness, anguish or metaphysical doubt; nor do they comment on social relations, bureaucracy, industrial society or the history of the 20th century. To do any of these things they would have to be concerned with consciousness. What they do is to demonstrate how alienation may provoke a longing for its own absolute form—which is mindlessness. This is the consistent truth demonstrated, rather than expressed, in Bacon's work.

The Truman Show explores the same theme. Read this website commentary on the film. When everything is done for you, mindlessness is the absolute form of alienation. And yet the director who made this film, chose to film it at Seaside.

Section 7

Obviously, towns in bottles are not what any of us has been trying for

After so much care, and so much thought and effort, and so much success, what is it about Seaside that remains somehow, not quite real, one would almost want to say "plastic"—if that were not so harsh a word.

Section 8

A partial solution to the problem

How may we all try, together, to solve this problem?

Here is where we might be able to contribute and feel progress can be made.

The geometry of the real McCoy

The deep geometry of the space and building volumes in traditional towns, very dear to all of us, and certainly dear also to new urbanists, is not yet fully understood. It seems as though it can be approximated successfully, by a formula, but this is really not so. Recent advances in theory, suggest that the essence of a living structure (in a building or a town) is something which we may consider as a generated structure—It is the geometry of an unfolded generated structure which is simply unattainable in a Master Plan, no matter how brilliant the master plan. A full description of what we mean by a generated structure can be read in Book 2 of the Nature of Order. Very briefly said, a generated town plan is not set from the outset, but unfolds dynamically, so that at any point in time the number of decisions to be made is small and manageable. The complexity of those decisions can be grasped and handled adequately. These decisions become the context for the next set of decisions. Although the time factor can be compressed, the all-at-one-go simply does not work.It is the generated nature of the structure that will allow for the complexity that is required in a town plan that works.

An example of a generated structure may be seen in our own Eishin project in Japan: a highly formal project, quite large—about nine blocks in area—but with a generative process at its base that allows public space and building masses to form coherent space and coherent physical entities, step-by-step, under guidelines which focus on the production of positive space at every moment.

The physical character of this kind of thing, is clearly visible in the following photographs.

Overviews of the campus, showing the different approach to space which arises when the structure is generated step by step, not planned

The theory of this kind of generated structure has only recently been fully understood, and was first announced at Alexander's November lecture to the Stanford Computer Science Department (November 2000). This theory is surprising and we believe it will be very useful to our common effort.

Our second answer to the question of how to do better, is simply to list certain recommended modifications of attitude, whenever we are doing projects:

- We need to keep the ability of the pattern books to influence large areas as one whole, so that genuinely large parts of the built environment are brought under their influence.

- We need to make sure that the application of patterns is through free action and decision making, not coerced.

- We need a more generative approach, in which individuals are given more ability to make their own environments for themselves, without necessarily using the services of architects in present-day forms.

- We need a generative approach, also, to the streets and public spaces, so that these, also, can be come a product of joint action in the community.

- We need a far more integrated relation between builders and architects, so that not only architects, but builders, too, can work directly with clients under the impact of generative schemes, to create a more flexible, more organic, and ultimately more endearing kind of order.

- We need far more access to slow piecemeal development of positive space, so that every act of building or improvement results in an improvement in the positive and felt character of outdoor space.

- On the whole, the environment should be less controlled, and more spontaneous.

- When rules have to be used, they should be more like inteional rules, not such hard and fast geometric doctrines.

- The role of the developer must be carefully, and radically re-examined, and we should try to find ways of cooperating with those few developers who operate from conscience (Robert Davis may be an example), to find ways of formulating an ethic for developers which does not allow interference between money, control, and the desire for genuine life and spontaneity in the environment. This needs a kind of hippocratic oath for developers; but the contents of such an oath have not yet been written or even formulated.

Introduction

The effort to make cities better, and to move away from the desert of urbanization familiar in mid 20th-century world, was inspired by various critical thinkers, architects and urbanists, who pointed out that traditional societies, traditional values, and classical traditional architecture all contained vital knowledge that was not ephemeral, but more or less permanent, and culture-independent: and therefore valid for our towns and buildings today, and in the future, just as much as it had been in earlier ages.

In the decade after the appearance of the pattern language, this was seen clearly, and independently, by a variety of architects in different countries, including Andres Duany, Leon Krier, Dan Solomon, various anthropologists, by planners such as Jane Jacobs, and then by many others, in the period from 1980 to the end of the century.

Section 1

Duany's most important accomplishment

The extraordinary contribution made by Duany was that he took the concept of patterns and pattern languages, and created a simple, and operationally feasible way of introducing this concept into effective town-planning procedure, consistent with United States conditions.

Don't just talk, do it. Talk, as we all know, comes cheap. Andres has gone to where the rubber hits the road, worked, confronted, composed with the forces in play. In twenty years with various associates he has designed over 80 new towns and revitalization projects for existing communities. Eighty real flesh and blood communities is a lot.

Visible in a number of pattern books composed specially for these different communities (see, for example, the Bedford pattern book for Bedford, in Pittsburgh ), the treatment of patterns in these plans is extraordinarily detailed, covering roads, lots, gardens, house volumes, style, massing, windows, architectural details.

......

......

Excerpts from the Bedford pattern book

It is fair to say that Duany's work, and the work of CNU that in large measure originates with his contribution, has altered, and will continue to alter, the American landscape. In spite of carping by others, one cannot get away from this fact.

That is a truly extraordinary accomplishment.

There is, also, considerable detail which came with this broad program, and which was, once again, made by Duany into something recognizable to the American public.

Our sacred cow: the car. Duany is clear that it is the public realm—the walkable public realm—that requires the most Tender Loving Care in community projects and that the power that has slid over to the traffic engineer must be rewon. One telling number from Duany's writings is that eliminating the need for one more car in a family (typically eating up around $5000 a year) will be the equivalent of that family's capacity of taking on a $50,000 mortgage. And we don't need new urbanists to tell us that our towns treat our cars better then they treat us.

A social and administrative process. To get real things done in the real world, different stakeholders must have their say. Duany's charrette process allows for client involvement, voicing of concerns, shared emergence of priorities, and "buy-in" for the plans and codes that will guide the design process. The "codes" that emerge from the charette and from study are project specific. They consider local architectural traditions and building techniques that will be work into exisiting zoning ordinances.

A sense of place. Duany struggles as all of us who are concerned with the built environment with a sense of place which comes from, among other factors, a balance of privacy and community. The Ahwahnee Principles (focusing on human scale, diversity, complexity, process of involvement) animate his work. His plans include neighborhoods that are easily walkable, finite with a definite character, mixed uses, complex and multipurpose grid streets networks, housing for different economic levels. He made incredible efforts to actually figure out the geometry. To have a sense of place is to have a sense of space. To give an example of one pattern in frequent use,

is that for every foot of vertical space there ought to be no more than 6 feet of horizontal space. In other words, the street width as measured from building front to building front should not exceed six times the height of the buildings.

Work with what you've got and push for bigger change. Duany is a realist. He works with what is there and pushes on the boundaries. While accepting the existing codes he lobbies for better ones. He advocates replacing codes based on functional separation with codes based on typological compatibility. He knows that specialized land use districts are almost always unnecessary. As long as the buildings along a stretch of street are compatible in shape and size,similar in site configuration, and follow the same disposition relative to the street, what functions go in them are of not great concern.

Duany's realistic problem solving is creative. The plan for the transfer of development rights for Hillsborough County, Florida is most impressive.

Altogether, the track record of study, action, and implementation is remarkable.

Section 2

Duany's most serious shortcoming

The greatest weakness, without a doubt, is the failure of Duany, and indeed of other CNU affiliates, to recognize the devastating effect of development, and of the developer, on the American landscape, and on the world landscape.

It is of course, a matter of practicality. If you want to affect things, go to the people who have the power and financial might, and try to persuade them. Andres Duany, Dan Solomon, Raymond Gindroz, Peter Calthorpe, have all tailored their activities to the existence of developers, without ever—apparently—grasping the extent to which this affiliation requires giving up on the fundamental processes which give life to the environment—the genuine fine grained participation of people themselves, and the creation of a world in which human intimacy is reflected in their production, in the absurd, charming, and often deeply adapted form of the buildings they create. The buildings made by a developer—even if acting within an imposed pattern book—cannot be well adapted, because the process stems from different motivations.

The greatest shortcoming of Duany (and CNU) is their failure to recognize that the form and complexity of the traditional town comes from (and can only come from) the process which generated it. Process and result can not be separated. Even with the charette approach to involve more stakeholders and the deliberate use of several architects to produce variation, the new urbanist developments are born from a process of a master scheme of blueprint, banking, permissions, construction. The expenditures of money and the decisions are not at the fine grained level of the spontaneous and free actual user. The process is guided by a monolithic need for control and restrictive covenants that protect the financial backers. It is inescapable that this process will lead to a different end result.

Section 3

Seaside, Florida

Duany's most well known project, at least until now, has been Seaside. Seaside is a town of some 4000 houses or households; many occupied at first as summer places, and then filled more as people chose to spend more of the year there.

Robert Davis, the developer of Seaside, has spent the better part of his life making this project, and trying, as best he can, to follow principles of community, discussion, town meetings, and to create a comfortable human atmosphere in which people can feel at home.

Davis among developers, is remarkable. He is marked by idealism, and moved by idealism. He has devoted his life to the creation of a modern American utopia, at least within the framework offered by contemporary American society and the current-day ideas of the flow of property and money.

To provide the physical layout and backdrop for Seaside, Duany made the first of his pattern books: a system of codes prescribing in considerable detail, the placing of buildings, setbacks, lots lines, fences, road widths, style even, window design, and so forth.

As far as one might hope, this has been successsful.

......

......

views of Seaside

Four views of Ruskin Place

Section 4

What does Seaside do and achieve?

First of, there is a humane environment, pleasant, avoiding many of the mishaps and ugliness of modern American development. It has charm. It has some atmosphere.

From a technical point of view, what is important, is simply the fact that the architect has achieved control over a very large area—some 600 acres: has created some degree of freedom and variation within that 600 acres; and has succeeded, in regulating, also, so that roads and streets are better scaled, there is some sense of pleasant architectural detail—white fences, good windows, and so on.

The scale is pleasant—and so this one architect (he would call himself a planner)—has asserted his design awareness over more than a thousand buildings, and has done so in a way that he can be proud of.To manage to have an effect on a very large number of buildings, without personally designing them, and yet to be concerned with the architecture—to achieve a certain coherence, scale, and pleasantness in them, together with sensible patterns carefully controlled—all that is an amazing achievement.

We take our hats off to Andres.

We all, members of the profession, need to exercise our action at this level. if each architect in the world were able to influence, in a positive fashion, such a relatively large area, the world would indeed be a better place, and the 500,000 to 1,000,000 architects in the world would then be able to have an effect on a major portion of the world's inhabited surface.

All that is immensely positive. It is an amazing achievement!

So where are the shortfalls?

Section 5

What does Seaside not achieve?

In order to achieve this very large, and humane effect, Andres has used what is a partly mechanical method. He has therefore been forced, in this first round of experiments (we take Seaside as an example only: the other projects work in roughly similar ways), to make a somewhat mechanical version of the ideal.

It is the nature of this "mechanical" aspect which has to be examined carefully.

In essence it consists of making a rigid framework, and allowing, then considerable individual variation within it. But the carcase, the street grid, is rigid: it does not arise from the give and take of real events. In this regard it is unlike an organic community. It is as if one were to have a rigid mechanical skeleton and hang variational flesh on it. That is not the same as making a coherent whole, in which the public space arises organically from detailed, and subtle adaptations to terrain, human idiosyncracy, individual trees, accidental paths, and so on.

And there follows from this a slightly more problematic quality. The actual public space is not always positive. It has not been lovingly crafted and shaped, because in the process followed, there was no opportunity to do such a thing.

The subtle mechanical character which underlies the production of the street grid, is visible, though, in a more disturbing quality. Occasionally one hears that there is something "unreal" about Seaside. Some of it is carping. Perhaps jealousy. But there is something about this comment that is real, and which goes to the very root of our current inability to make living space in towns.

Section 6

A view from the Press

Well-behaved dogs are allowed

This is the actual web caption placed with this picture, by the realtor who is renting the place!

DogGone Newsletter Vol.

8, No. 4, July/August 2000

A Seaside Utopia in Florida

In the movie, "The

Truman Show," Jim Carrey's character, Truman, lives in a utopian community,

unaware he was being filmed 24 hours a day. That visionary village really

exists. Seaside, Florida, where much of the movie was filmed, lies on  the Gulf of Mexico in Florida's panhandle,

tucked between Grayton Beach and Seagrove Beach. Pet owners can't rent

Truman's house (though you can photograph its exterior), but lucky dogs and

their owners can stay in a gorgeous waterfront $2-million plus vacation home.

It's virtually the only Seaside rental that will accept pets.

the Gulf of Mexico in Florida's panhandle,

tucked between Grayton Beach and Seagrove Beach. Pet owners can't rent

Truman's house (though you can photograph its exterior), but lucky dogs and

their owners can stay in a gorgeous waterfront $2-million plus vacation home.

It's virtually the only Seaside rental that will accept pets.

Idyll-By-The-Sea is a vacation rental cottage (it's really too

luxurious to be called a cottage) owned by Carol Irvine, Jerry Jongerius and

their German Shepherd Dog, Jackie. They are happy to rent their little

Shangri-La to owners of perfectly behaved pooches. The home's hardwood floors

tolerate sandy paws and dog sheets are provided to protect the furnishings.

And Idyll-By-The-Sea is well furnished, indeed. You can tell the owner's

business is antiques and interior design. The beach house is a comfortable mix

of new and old, with just the right touch of whimsy for a relaxed feel.

Thankfully, there's not a shred of Salvation Army style that pervades many

rental units I've leased over the years. Of course, the rental fee reflects

this. Idyll-By-The-Sea goes for $724-$874 per night.

Wendy Ballard

Reference to the film The Truman Show is not meant to be a facile criticism, but a genuine worry that all is not quite well.

The careful choice of Seaside as an ideal film set for the surreal film of alienation and falseness and image-production is not an accident. The choice of Jim Carrey as the hero is not an accident either. Curiously, to make our point, we turn to a passage about contemporary alienation hiding in a bland exterior, written by the art critic, John Berger in his essay on Francis Bacon. Consider what he says in the following quote:

Bacon's art is, in effect, conformist. It is not with Goya or the early Eisenstein that he should be compared, but with Walt Disney. Both men make propositions about the alienated behaviour of our societies; and both, in a different way, persuade the viewer to accept what is. Disney makes alienated behaviour look funny and sentimental and therefore, acceptable. Bacon interprets such behaviour in terms of the worst possible having already happened, and so proposes that both refusal and hope are pointless. The surprising formal similarities of their work—the way limbs are distorted, the overall shapes of bodies, the relation of figures to background and to one another, the use of neat tailor's clothes, the gesture of hands, the range of colours used—are the result of both men having complementary attitudes to the same crisis.

Disney's world is also charged with vain violence. The ultimate catastrophe is always in the offing. His creatures have both personality and nervous reactions: what they lack (almost) is mind. If, before a cartoon sequence by Disney, one read and believed the caption, "There is nothing else," the film would strike us as horrifically as a painting by Bacon.

Bacon's paintings do not comment, as is often said, on any actual experience of loneliness, anguish or metaphysical doubt; nor do they comment on social relations, bureaucracy, industrial society or the history of the 20th century. To do any of these things they would have to be concerned with consciousness. What they do is to demonstrate how alienation may provoke a longing for its own absolute form—which is mindlessness. This is the consistent truth demonstrated, rather than expressed, in Bacon's work.

The Truman Show explores the same theme. Read this website commentary on the film. When everything is done for you, mindlessness is the absolute form of alienation. And yet the director who made this film, chose to film it at Seaside.

Section 7

Obviously, towns in bottles are not what any of us has been trying for

After so much care, and so much thought and effort, and so much success, what is it about Seaside that remains somehow, not quite real, one would almost want to say "plastic"—if that were not so harsh a word.

Section 8

A partial solution to the problem

How may we all try, together, to solve this problem?

Here is where we might be able to contribute and feel progress can be made.

The geometry of the real McCoy

The deep geometry of the space and building volumes in traditional towns, very dear to all of us, and certainly dear also to new urbanists, is not yet fully understood. It seems as though it can be approximated successfully, by a formula, but this is really not so. Recent advances in theory, suggest that the essence of a living structure (in a building or a town) is something which we may consider as a generated structure—It is the geometry of an unfolded generated structure which is simply unattainable in a Master Plan, no matter how brilliant the master plan. A full description of what we mean by a generated structure can be read in Book 2 of the Nature of Order. Very briefly said, a generated town plan is not set from the outset, but unfolds dynamically, so that at any point in time the number of decisions to be made is small and manageable. The complexity of those decisions can be grasped and handled adequately. These decisions become the context for the next set of decisions. Although the time factor can be compressed, the all-at-one-go simply does not work.It is the generated nature of the structure that will allow for the complexity that is required in a town plan that works.

An example of a generated structure may be seen in our own Eishin project in Japan: a highly formal project, quite large—about nine blocks in area—but with a generative process at its base that allows public space and building masses to form coherent space and coherent physical entities, step-by-step, under guidelines which focus on the production of positive space at every moment.

The physical character of this kind of thing, is clearly visible in the following photographs.

Overviews of the campus, showing the different approach to space which arises when the structure is generated step by step, not planned

The theory of this kind of generated structure has only recently been fully understood, and was first announced at Alexander's November lecture to the Stanford Computer Science Department (November 2000). This theory is surprising and we believe it will be very useful to our common effort.

Our second answer to the question of how to do better, is simply to list certain recommended modifications of attitude, whenever we are doing projects:

- We need to keep the ability of the pattern books to influence large areas as one whole, so that genuinely large parts of the built environment are brought under their influence.

- We need to make sure that the application of patterns is through free action and decision making, not coerced.

- We need a more generative approach, in which individuals are given more ability to make their own environments for themselves, without necessarily using the services of architects in present-day forms.

- We need a generative approach, also, to the streets and public spaces, so that these, also, can be come a product of joint action in the community.

- We need a far more integrated relation between builders and architects, so that not only architects, but builders, too, can work directly with clients under the impact of generative schemes, to create a more flexible, more organic, and ultimately more endearing kind of order.

- We need far more access to slow piecemeal development of positive space, so that every act of building or improvement results in an improvement in the positive and felt character of outdoor space.

- On the whole, the environment should be less controlled, and more spontaneous.

- When rules have to be used, they should be more like inteional rules, not such hard and fast geometric doctrines.

- The role of the developer must be carefully, and radically re-examined, and we should try to find ways of cooperating with those few developers who operate from conscience (Robert Davis may be an example), to find ways of formulating an ethic for developers which does not allow interference between money, control, and the desire for genuine life and spontaneity in the environment. This needs a kind of hippocratic oath for developers; but the contents of such an oath have not yet been written or even formulated.

The effort to make cities better, and to move away from the desert of urbanization familiar in mid 20th-century world, was inspired by various critical thinkers, architects and urbanists, who pointed out that traditional societies, traditional values, and classical traditional architecture all contained vital knowledge that was not ephemeral, but more or less permanent, and culture-independent: and therefore valid for our towns and buildings today, and in the future, just as much as it had been in earlier ages.

In the decade after the appearance of the pattern language, this was seen clearly, and independently, by a variety of architects in different countries, including Andres Duany, Leon Krier, Dan Solomon, various anthropologists, by planners such as Jane Jacobs, and then by many others, in the period from 1980 to the end of the century.

Section 1

Duany's most important accomplishment

The extraordinary contribution made by Duany was that he took the concept of patterns and pattern languages, and created a simple, and operationally feasible way of introducing this concept into effective town-planning procedure, consistent with United States conditions.

Don't just talk, do it. Talk, as we all know, comes cheap. Andres has gone to where the rubber hits the road, worked, confronted, composed with the forces in play. In twenty years with various associates he has designed over 80 new towns and revitalization projects for existing communities. Eighty real flesh and blood communities is a lot.

Visible in a number of pattern books composed specially for these different communities (see, for example, the Bedford pattern book for Bedford, in Pittsburgh ), the treatment of patterns in these plans is extraordinarily detailed, covering roads, lots, gardens, house volumes, style, massing, windows, architectural details.

......

......

Excerpts from the Bedford pattern book

It is fair to say that Duany's work, and the work of CNU that in large measure originates with his contribution, has altered, and will continue to alter, the American landscape. In spite of carping by others, one cannot get away from this fact.

That is a truly extraordinary accomplishment.

There is, also, considerable detail which came with this broad program, and which was, once again, made by Duany into something recognizable to the American public.

Our sacred cow: the car. Duany is clear that it is the public realm—the walkable public realm—that requires the most Tender Loving Care in community projects and that the power that has slid over to the traffic engineer must be rewon. One telling number from Duany's writings is that eliminating the need for one more car in a family (typically eating up around $5000 a year) will be the equivalent of that family's capacity of taking on a $50,000 mortgage. And we don't need new urbanists to tell us that our towns treat our cars better then they treat us.

A social and administrative process. To get real things done in the real world, different stakeholders must have their say. Duany's charrette process allows for client involvement, voicing of concerns, shared emergence of priorities, and "buy-in" for the plans and codes that will guide the design process. The "codes" that emerge from the charette and from study are project specific. They consider local architectural traditions and building techniques that will be work into exisiting zoning ordinances.

A sense of place. Duany struggles as all of us who are concerned with the built environment with a sense of place which comes from, among other factors, a balance of privacy and community. The Ahwahnee Principles (focusing on human scale, diversity, complexity, process of involvement) animate his work. His plans include neighborhoods that are easily walkable, finite with a definite character, mixed uses, complex and multipurpose grid streets networks, housing for different economic levels. He made incredible efforts to actually figure out the geometry. To have a sense of place is to have a sense of space. To give an example of one pattern in frequent use,

is that for every foot of vertical space there ought to be no more than 6 feet of horizontal space. In other words, the street width as measured from building front to building front should not exceed six times the height of the buildings.

Work with what you've got and push for bigger change. Duany is a realist. He works with what is there and pushes on the boundaries. While accepting the existing codes he lobbies for better ones. He advocates replacing codes based on functional separation with codes based on typological compatibility. He knows that specialized land use districts are almost always unnecessary. As long as the buildings along a stretch of street are compatible in shape and size,similar in site configuration, and follow the same disposition relative to the street, what functions go in them are of not great concern.

Duany's realistic problem solving is creative. The plan for the transfer of development rights for Hillsborough County, Florida is most impressive.

Altogether, the track record of study, action, and implementation is remarkable.

Section 2

Duany's most serious shortcoming

The greatest weakness, without a doubt, is the failure of Duany, and indeed of other CNU affiliates, to recognize the devastating effect of development, and of the developer, on the American landscape, and on the world landscape.

It is of course, a matter of practicality. If you want to affect things, go to the people who have the power and financial might, and try to persuade them. Andres Duany, Dan Solomon, Raymond Gindroz, Peter Calthorpe, have all tailored their activities to the existence of developers, without ever—apparently—grasping the extent to which this affiliation requires giving up on the fundamental processes which give life to the environment—the genuine fine grained participation of people themselves, and the creation of a world in which human intimacy is reflected in their production, in the absurd, charming, and often deeply adapted form of the buildings they create. The buildings made by a developer—even if acting within an imposed pattern book—cannot be well adapted, because the process stems from different motivations.

The greatest shortcoming of Duany (and CNU) is their failure to recognize that the form and complexity of the traditional town comes from (and can only come from) the process which generated it. Process and result can not be separated. Even with the charette approach to involve more stakeholders and the deliberate use of several architects to produce variation, the new urbanist developments are born from a process of a master scheme of blueprint, banking, permissions, construction. The expenditures of money and the decisions are not at the fine grained level of the spontaneous and free actual user. The process is guided by a monolithic need for control and restrictive covenants that protect the financial backers. It is inescapable that this process will lead to a different end result.

Section 3

Seaside, Florida

Duany's most well known project, at least until now, has been Seaside. Seaside is a town of some 4000 houses or households; many occupied at first as summer places, and then filled more as people chose to spend more of the year there.

Robert Davis, the developer of Seaside, has spent the better part of his life making this project, and trying, as best he can, to follow principles of community, discussion, town meetings, and to create a comfortable human atmosphere in which people can feel at home.

Davis among developers, is remarkable. He is marked by idealism, and moved by idealism. He has devoted his life to the creation of a modern American utopia, at least within the framework offered by contemporary American society and the current-day ideas of the flow of property and money.

To provide the physical layout and backdrop for Seaside, Duany made the first of his pattern books: a system of codes prescribing in considerable detail, the placing of buildings, setbacks, lots lines, fences, road widths, style even, window design, and so forth.

As far as one might hope, this has been successsful.

......

......

views of Seaside

Four views of Ruskin Place

Section 4

What does Seaside do and achieve?

First of, there is a humane environment, pleasant, avoiding many of the mishaps and ugliness of modern American development. It has charm. It has some atmosphere.

From a technical point of view, what is important, is simply the fact that the architect has achieved control over a very large area—some 600 acres: has created some degree of freedom and variation within that 600 acres; and has succeeded, in regulating, also, so that roads and streets are better scaled, there is some sense of pleasant architectural detail—white fences, good windows, and so on.

The scale is pleasant—and so this one architect (he would call himself a planner)—has asserted his design awareness over more than a thousand buildings, and has done so in a way that he can be proud of.To manage to have an effect on a very large number of buildings, without personally designing them, and yet to be concerned with the architecture—to achieve a certain coherence, scale, and pleasantness in them, together with sensible patterns carefully controlled—all that is an amazing achievement.

We take our hats off to Andres.

We all, members of the profession, need to exercise our action at this level. if each architect in the world were able to influence, in a positive fashion, such a relatively large area, the world would indeed be a better place, and the 500,000 to 1,000,000 architects in the world would then be able to have an effect on a major portion of the world's inhabited surface.

All that is immensely positive. It is an amazing achievement!

So where are the shortfalls?

Section 5

What does Seaside not achieve?

In order to achieve this very large, and humane effect, Andres has used what is a partly mechanical method. He has therefore been forced, in this first round of experiments (we take Seaside as an example only: the other projects work in roughly similar ways), to make a somewhat mechanical version of the ideal.

It is the nature of this "mechanical" aspect which has to be examined carefully.

In essence it consists of making a rigid framework, and allowing, then considerable individual variation within it. But the carcase, the street grid, is rigid: it does not arise from the give and take of real events. In this regard it is unlike an organic community. It is as if one were to have a rigid mechanical skeleton and hang variational flesh on it. That is not the same as making a coherent whole, in which the public space arises organically from detailed, and subtle adaptations to terrain, human idiosyncracy, individual trees, accidental paths, and so on.

And there follows from this a slightly more problematic quality. The actual public space is not always positive. It has not been lovingly crafted and shaped, because in the process followed, there was no opportunity to do such a thing.

The subtle mechanical character which underlies the production of the street grid, is visible, though, in a more disturbing quality. Occasionally one hears that there is something "unreal" about Seaside. Some of it is carping. Perhaps jealousy. But there is something about this comment that is real, and which goes to the very root of our current inability to make living space in towns.

Section 6

A view from the Press

Well-behaved dogs are allowed

This is the actual web caption placed with this picture, by the realtor who is renting the place!

DogGone Newsletter Vol.

8, No. 4, July/August 2000

A Seaside Utopia in Florida

In the movie, "The

Truman Show," Jim Carrey's character, Truman, lives in a utopian community,

unaware he was being filmed 24 hours a day. That visionary village really

exists. Seaside, Florida, where much of the movie was filmed, lies on  the Gulf of Mexico in Florida's panhandle,

tucked between Grayton Beach and Seagrove Beach. Pet owners can't rent

Truman's house (though you can photograph its exterior), but lucky dogs and

their owners can stay in a gorgeous waterfront $2-million plus vacation home.

It's virtually the only Seaside rental that will accept pets.

the Gulf of Mexico in Florida's panhandle,

tucked between Grayton Beach and Seagrove Beach. Pet owners can't rent

Truman's house (though you can photograph its exterior), but lucky dogs and

their owners can stay in a gorgeous waterfront $2-million plus vacation home.

It's virtually the only Seaside rental that will accept pets.

Idyll-By-The-Sea is a vacation rental cottage (it's really too

luxurious to be called a cottage) owned by Carol Irvine, Jerry Jongerius and

their German Shepherd Dog, Jackie. They are happy to rent their little

Shangri-La to owners of perfectly behaved pooches. The home's hardwood floors

tolerate sandy paws and dog sheets are provided to protect the furnishings.

And Idyll-By-The-Sea is well furnished, indeed. You can tell the owner's

business is antiques and interior design. The beach house is a comfortable mix

of new and old, with just the right touch of whimsy for a relaxed feel.

Thankfully, there's not a shred of Salvation Army style that pervades many

rental units I've leased over the years. Of course, the rental fee reflects

this. Idyll-By-The-Sea goes for $724-$874 per night.

Wendy Ballard

Reference to the film The Truman Show is not meant to be a facile criticism, but a genuine worry that all is not quite well.

The careful choice of Seaside as an ideal film set for the surreal film of alienation and falseness and image-production is not an accident. The choice of Jim Carrey as the hero is not an accident either. Curiously, to make our point, we turn to a passage about contemporary alienation hiding in a bland exterior, written by the art critic, John Berger in his essay on Francis Bacon. Consider what he says in the following quote:

Bacon's art is, in effect, conformist. It is not with Goya or the early Eisenstein that he should be compared, but with Walt Disney. Both men make propositions about the alienated behaviour of our societies; and both, in a different way, persuade the viewer to accept what is. Disney makes alienated behaviour look funny and sentimental and therefore, acceptable. Bacon interprets such behaviour in terms of the worst possible having already happened, and so proposes that both refusal and hope are pointless. The surprising formal similarities of their work—the way limbs are distorted, the overall shapes of bodies, the relation of figures to background and to one another, the use of neat tailor's clothes, the gesture of hands, the range of colours used—are the result of both men having complementary attitudes to the same crisis.

Disney's world is also charged with vain violence. The ultimate catastrophe is always in the offing. His creatures have both personality and nervous reactions: what they lack (almost) is mind. If, before a cartoon sequence by Disney, one read and believed the caption, "There is nothing else," the film would strike us as horrifically as a painting by Bacon.

Bacon's paintings do not comment, as is often said, on any actual experience of loneliness, anguish or metaphysical doubt; nor do they comment on social relations, bureaucracy, industrial society or the history of the 20th century. To do any of these things they would have to be concerned with consciousness. What they do is to demonstrate how alienation may provoke a longing for its own absolute form—which is mindlessness. This is the consistent truth demonstrated, rather than expressed, in Bacon's work.

The Truman Show explores the same theme. Read this website commentary on the film. When everything is done for you, mindlessness is the absolute form of alienation. And yet the director who made this film, chose to film it at Seaside.

Section 7

Obviously, towns in bottles are not what any of us has been trying for

After so much care, and so much thought and effort, and so much success, what is it about Seaside that remains somehow, not quite real, one would almost want to say "plastic"—if that were not so harsh a word.

Section 8

A partial solution to the problem

How may we all try, together, to solve this problem?

Here is where we might be able to contribute and feel progress can be made.

The geometry of the real McCoy

The deep geometry of the space and building volumes in traditional towns, very dear to all of us, and certainly dear also to new urbanists, is not yet fully understood. It seems as though it can be approximated successfully, by a formula, but this is really not so. Recent advances in theory, suggest that the essence of a living structure (in a building or a town) is something which we may consider as a generated structure—It is the geometry of an unfolded generated structure which is simply unattainable in a Master Plan, no matter how brilliant the master plan. A full description of what we mean by a generated structure can be read in Book 2 of the Nature of Order. Very briefly said, a generated town plan is not set from the outset, but unfolds dynamically, so that at any point in time the number of decisions to be made is small and manageable. The complexity of those decisions can be grasped and handled adequately. These decisions become the context for the next set of decisions. Although the time factor can be compressed, the all-at-one-go simply does not work.It is the generated nature of the structure that will allow for the complexity that is required in a town plan that works.

An example of a generated structure may be seen in our own Eishin project in Japan: a highly formal project, quite large—about nine blocks in area—but with a generative process at its base that allows public space and building masses to form coherent space and coherent physical entities, step-by-step, under guidelines which focus on the production of positive space at every moment.

The physical character of this kind of thing, is clearly visible in the following photographs.

Overviews of the campus, showing the different approach to space which arises when the structure is generated step by step, not planned

The theory of this kind of generated structure has only recently been fully understood, and was first announced at Alexander's November lecture to the Stanford Computer Science Department (November 2000). This theory is surprising and we believe it will be very useful to our common effort.

Our second answer to the question of how to do better, is simply to list certain recommended modifications of attitude, whenever we are doing projects:

- We need to keep the ability of the pattern books to influence large areas as one whole, so that genuinely large parts of the built environment are brought under their influence.

- We need to make sure that the application of patterns is through free action and decision making, not coerced.

- We need a more generative approach, in which individuals are given more ability to make their own environments for themselves, without necessarily using the services of architects in present-day forms.

- We need a generative approach, also, to the streets and public spaces, so that these, also, can be come a product of joint action in the community.

- We need a far more integrated relation between builders and architects, so that not only architects, but builders, too, can work directly with clients under the impact of generative schemes, to create a more flexible, more organic, and ultimately more endearing kind of order.

- We need far more access to slow piecemeal development of positive space, so that every act of building or improvement results in an improvement in the positive and felt character of outdoor space.

- On the whole, the environment should be less controlled, and more spontaneous.

- When rules have to be used, they should be more like inteional rules, not such hard and fast geometric doctrines.

- The role of the developer must be carefully, and radically re-examined, and we should try to find ways of cooperating with those few developers who operate from conscience (Robert Davis may be an example), to find ways of formulating an ethic for developers which does not allow interference between money, control, and the desire for genuine life and spontaneity in the environment. This needs a kind of hippocratic oath for developers; but the contents of such an oath have not yet been written or even formulated.

Duany's most important accomplishment

The extraordinary contribution made by Duany was that he took the concept of patterns and pattern languages, and created a simple, and operationally feasible way of introducing this concept into effective town-planning procedure, consistent with United States conditions.

Don't just talk, do it. Talk, as we all know, comes cheap. Andres has gone to where the rubber hits the road, worked, confronted, composed with the forces in play. In twenty years with various associates he has designed over 80 new towns and revitalization projects for existing communities. Eighty real flesh and blood communities is a lot.

Visible in a number of pattern books composed specially for these different communities (see, for example, the Bedford pattern book for Bedford, in Pittsburgh ), the treatment of patterns in these plans is extraordinarily detailed, covering roads, lots, gardens, house volumes, style, massing, windows, architectural details.

......

......

Excerpts from the Bedford pattern book

It is fair to say that Duany's work, and the work of CNU that in large measure originates with his contribution, has altered, and will continue to alter, the American landscape. In spite of carping by others, one cannot get away from this fact.

That is a truly extraordinary accomplishment.

There is, also, considerable detail which came with this broad program, and which was, once again, made by Duany into something recognizable to the American public.

Our sacred cow: the car. Duany is clear that it is the public realm—the walkable public realm—that requires the most Tender Loving Care in community projects and that the power that has slid over to the traffic engineer must be rewon. One telling number from Duany's writings is that eliminating the need for one more car in a family (typically eating up around $5000 a year) will be the equivalent of that family's capacity of taking on a $50,000 mortgage. And we don't need new urbanists to tell us that our towns treat our cars better then they treat us.

A social and administrative process. To get real things done in the real world, different stakeholders must have their say. Duany's charrette process allows for client involvement, voicing of concerns, shared emergence of priorities, and "buy-in" for the plans and codes that will guide the design process. The "codes" that emerge from the charette and from study are project specific. They consider local architectural traditions and building techniques that will be work into exisiting zoning ordinances.

A sense of place. Duany struggles as all of us who are concerned with the built environment with a sense of place which comes from, among other factors, a balance of privacy and community. The Ahwahnee Principles (focusing on human scale, diversity, complexity, process of involvement) animate his work. His plans include neighborhoods that are easily walkable, finite with a definite character, mixed uses, complex and multipurpose grid streets networks, housing for different economic levels. He made incredible efforts to actually figure out the geometry. To have a sense of place is to have a sense of space. To give an example of one pattern in frequent use,

is that for every foot of vertical space there ought to be no more than 6 feet of horizontal space. In other words, the street width as measured from building front to building front should not exceed six times the height of the buildings.

Work with what you've got and push for bigger change. Duany is a realist. He works with what is there and pushes on the boundaries. While accepting the existing codes he lobbies for better ones. He advocates replacing codes based on functional separation with codes based on typological compatibility. He knows that specialized land use districts are almost always unnecessary. As long as the buildings along a stretch of street are compatible in shape and size,similar in site configuration, and follow the same disposition relative to the street, what functions go in them are of not great concern.

Duany's realistic problem solving is creative. The plan for the transfer of development rights for Hillsborough County, Florida is most impressive.

Altogether, the track record of study, action, and implementation is remarkable.

Section 2

Duany's most serious shortcoming

The greatest weakness, without a doubt, is the failure of Duany, and indeed of other CNU affiliates, to recognize the devastating effect of development, and of the developer, on the American landscape, and on the world landscape.

It is of course, a matter of practicality. If you want to affect things, go to the people who have the power and financial might, and try to persuade them. Andres Duany, Dan Solomon, Raymond Gindroz, Peter Calthorpe, have all tailored their activities to the existence of developers, without ever—apparently—grasping the extent to which this affiliation requires giving up on the fundamental processes which give life to the environment—the genuine fine grained participation of people themselves, and the creation of a world in which human intimacy is reflected in their production, in the absurd, charming, and often deeply adapted form of the buildings they create. The buildings made by a developer—even if acting within an imposed pattern book—cannot be well adapted, because the process stems from different motivations.

The greatest shortcoming of Duany (and CNU) is their failure to recognize that the form and complexity of the traditional town comes from (and can only come from) the process which generated it. Process and result can not be separated. Even with the charette approach to involve more stakeholders and the deliberate use of several architects to produce variation, the new urbanist developments are born from a process of a master scheme of blueprint, banking, permissions, construction. The expenditures of money and the decisions are not at the fine grained level of the spontaneous and free actual user. The process is guided by a monolithic need for control and restrictive covenants that protect the financial backers. It is inescapable that this process will lead to a different end result.

Section 3

Seaside, Florida

Duany's most well known project, at least until now, has been Seaside. Seaside is a town of some 4000 houses or households; many occupied at first as summer places, and then filled more as people chose to spend more of the year there.

Robert Davis, the developer of Seaside, has spent the better part of his life making this project, and trying, as best he can, to follow principles of community, discussion, town meetings, and to create a comfortable human atmosphere in which people can feel at home.

Davis among developers, is remarkable. He is marked by idealism, and moved by idealism. He has devoted his life to the creation of a modern American utopia, at least within the framework offered by contemporary American society and the current-day ideas of the flow of property and money.

To provide the physical layout and backdrop for Seaside, Duany made the first of his pattern books: a system of codes prescribing in considerable detail, the placing of buildings, setbacks, lots lines, fences, road widths, style even, window design, and so forth.

As far as one might hope, this has been successsful.

......

......

views of Seaside

Four views of Ruskin Place

Section 4

What does Seaside do and achieve?

First of, there is a humane environment, pleasant, avoiding many of the mishaps and ugliness of modern American development. It has charm. It has some atmosphere.

From a technical point of view, what is important, is simply the fact that the architect has achieved control over a very large area—some 600 acres: has created some degree of freedom and variation within that 600 acres; and has succeeded, in regulating, also, so that roads and streets are better scaled, there is some sense of pleasant architectural detail—white fences, good windows, and so on.

The scale is pleasant—and so this one architect (he would call himself a planner)—has asserted his design awareness over more than a thousand buildings, and has done so in a way that he can be proud of.To manage to have an effect on a very large number of buildings, without personally designing them, and yet to be concerned with the architecture—to achieve a certain coherence, scale, and pleasantness in them, together with sensible patterns carefully controlled—all that is an amazing achievement.

We take our hats off to Andres.

We all, members of the profession, need to exercise our action at this level. if each architect in the world were able to influence, in a positive fashion, such a relatively large area, the world would indeed be a better place, and the 500,000 to 1,000,000 architects in the world would then be able to have an effect on a major portion of the world's inhabited surface.

All that is immensely positive. It is an amazing achievement!

So where are the shortfalls?

Section 5

What does Seaside not achieve?

In order to achieve this very large, and humane effect, Andres has used what is a partly mechanical method. He has therefore been forced, in this first round of experiments (we take Seaside as an example only: the other projects work in roughly similar ways), to make a somewhat mechanical version of the ideal.

It is the nature of this "mechanical" aspect which has to be examined carefully.

In essence it consists of making a rigid framework, and allowing, then considerable individual variation within it. But the carcase, the street grid, is rigid: it does not arise from the give and take of real events. In this regard it is unlike an organic community. It is as if one were to have a rigid mechanical skeleton and hang variational flesh on it. That is not the same as making a coherent whole, in which the public space arises organically from detailed, and subtle adaptations to terrain, human idiosyncracy, individual trees, accidental paths, and so on.

And there follows from this a slightly more problematic quality. The actual public space is not always positive. It has not been lovingly crafted and shaped, because in the process followed, there was no opportunity to do such a thing.

The subtle mechanical character which underlies the production of the street grid, is visible, though, in a more disturbing quality. Occasionally one hears that there is something "unreal" about Seaside. Some of it is carping. Perhaps jealousy. But there is something about this comment that is real, and which goes to the very root of our current inability to make living space in towns.

Section 6

A view from the Press

Well-behaved dogs are allowed

This is the actual web caption placed with this picture, by the realtor who is renting the place!

DogGone Newsletter Vol.

8, No. 4, July/August 2000

A Seaside Utopia in Florida

In the movie, "The

Truman Show," Jim Carrey's character, Truman, lives in a utopian community,

unaware he was being filmed 24 hours a day. That visionary village really

exists. Seaside, Florida, where much of the movie was filmed, lies on  the Gulf of Mexico in Florida's panhandle,

tucked between Grayton Beach and Seagrove Beach. Pet owners can't rent

Truman's house (though you can photograph its exterior), but lucky dogs and

their owners can stay in a gorgeous waterfront $2-million plus vacation home.

It's virtually the only Seaside rental that will accept pets.

the Gulf of Mexico in Florida's panhandle,

tucked between Grayton Beach and Seagrove Beach. Pet owners can't rent

Truman's house (though you can photograph its exterior), but lucky dogs and

their owners can stay in a gorgeous waterfront $2-million plus vacation home.

It's virtually the only Seaside rental that will accept pets.

Idyll-By-The-Sea is a vacation rental cottage (it's really too

luxurious to be called a cottage) owned by Carol Irvine, Jerry Jongerius and

their German Shepherd Dog, Jackie. They are happy to rent their little

Shangri-La to owners of perfectly behaved pooches. The home's hardwood floors

tolerate sandy paws and dog sheets are provided to protect the furnishings.

And Idyll-By-The-Sea is well furnished, indeed. You can tell the owner's

business is antiques and interior design. The beach house is a comfortable mix

of new and old, with just the right touch of whimsy for a relaxed feel.

Thankfully, there's not a shred of Salvation Army style that pervades many

rental units I've leased over the years. Of course, the rental fee reflects

this. Idyll-By-The-Sea goes for $724-$874 per night.

Wendy Ballard

Reference to the film The Truman Show is not meant to be a facile criticism, but a genuine worry that all is not quite well.

The careful choice of Seaside as an ideal film set for the surreal film of alienation and falseness and image-production is not an accident. The choice of Jim Carrey as the hero is not an accident either. Curiously, to make our point, we turn to a passage about contemporary alienation hiding in a bland exterior, written by the art critic, John Berger in his essay on Francis Bacon. Consider what he says in the following quote:

Bacon's art is, in effect, conformist. It is not with Goya or the early Eisenstein that he should be compared, but with Walt Disney. Both men make propositions about the alienated behaviour of our societies; and both, in a different way, persuade the viewer to accept what is. Disney makes alienated behaviour look funny and sentimental and therefore, acceptable. Bacon interprets such behaviour in terms of the worst possible having already happened, and so proposes that both refusal and hope are pointless. The surprising formal similarities of their work—the way limbs are distorted, the overall shapes of bodies, the relation of figures to background and to one another, the use of neat tailor's clothes, the gesture of hands, the range of colours used—are the result of both men having complementary attitudes to the same crisis.

Disney's world is also charged with vain violence. The ultimate catastrophe is always in the offing. His creatures have both personality and nervous reactions: what they lack (almost) is mind. If, before a cartoon sequence by Disney, one read and believed the caption, "There is nothing else," the film would strike us as horrifically as a painting by Bacon.

Bacon's paintings do not comment, as is often said, on any actual experience of loneliness, anguish or metaphysical doubt; nor do they comment on social relations, bureaucracy, industrial society or the history of the 20th century. To do any of these things they would have to be concerned with consciousness. What they do is to demonstrate how alienation may provoke a longing for its own absolute form—which is mindlessness. This is the consistent truth demonstrated, rather than expressed, in Bacon's work.

The Truman Show explores the same theme. Read this website commentary on the film. When everything is done for you, mindlessness is the absolute form of alienation. And yet the director who made this film, chose to film it at Seaside.

Section 7

Obviously, towns in bottles are not what any of us has been trying for

After so much care, and so much thought and effort, and so much success, what is it about Seaside that remains somehow, not quite real, one would almost want to say "plastic"—if that were not so harsh a word.